Sharon vs. Sharon vs. Terry vs. Sorcery

- Lauren Higgs

- Oct 11, 2024

- 9 min read

We sincerely hope you're ready for a story that involves an eccentric heiress, robber barons, sorcery (that's right, we said "sorcery"), a disinterment, a duel, the first Black American millionaire, and more.

What does one even need to do to get ready for such a thing? Box breathing? Air punching? Neck rolls? Anyhow, prepare yourself to meet...

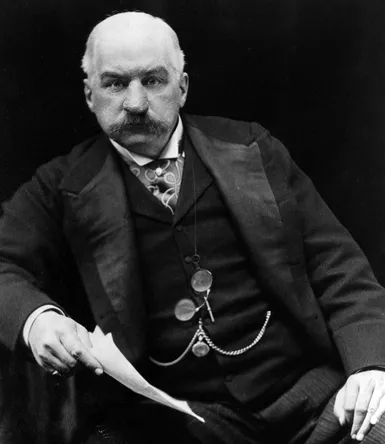

This guy. We're starting with him. Senator William Tang Sharon—named after the popular 70s space beverage—looked an awful lot like the Monopoly Man aka Mr. Monopoly aka Rich Uncle Moneybags.

And this is no coincidence. Just like John Pierpont Morgan, the man Mr. Monopoly was based on, Sharon was also a robber baron. The two men were contemporaries, though Sharon established his wealth and reputation on the burgeoning west coast of the United States, across the country from Ol' Pierpont.

The most important gallery of images we've ever created. Did you think the Monopoly Man had a monocle? You're not alone, but, alas, he did not.

William Sharon became wealthy via the Comstock Lode, a large cache of silver ore discovered in the Nevada mountains in 1859. (Say it "Ne-VA-duh" in your head, or somehow, somewhere, a Nevadan will know and get mad at you.) Around this time, Sharon met and married Maria Molloy, a Quebecois girl with whom he had five children, none of whom, sadly, were named after any kind of instant breakfast drink.

The Comstock Lode made a lot of folks wealthy as it turns out, one of whom was William Chapman Ralston, financier, and founder of the Bank of California. Ralston and William Sharon became business partners, and Ralston appointed Sharon to manage the Bank of California's Nevada interests.

Together, Ralston and Sharon controlled a majority interest in the silver mining operations of the American West and the two men became extremely wealthy. Ralston was not afraid of spending his vast fortune and was ultimately put into ruin when several large investments failed to produce and there was a run on his bank.

On 27 August 1875—the day following his personal financial collapse—Ralston's body was found in the San Francisco Bay, the victim of either an eerily timed stroke or suicide. When Ralston drowned, Sharon acquired many of his assets, including the multi-million dollar Palace Hotel of San Francisco.

At the time of Ralston's death, Sharon was a newly elected U.S. Senator, representing the state of Nevada (a state in which he more or less no longer resided). He was also recently widowed, his wife Maria having died of stomach cancer in May of the same year. Following his acquisition of Ralston's estate, Bill Sharon became the largest single tax payer (when he didn't attempt to evade paying them) in the state of California.

And, thus, rich, powerful, single and ready to mingle Bill Sharon, at the age of 54, became a little bit of a, eh... well... he was a little bit of a player, y'all.

Sharon liked the ladies, and the ladies, well, they really liked Sharon. Ahem, we mean Sharon's money. They really liked his money. He was rumored to have mistresses far and wide, and to spend extravagantly on his numerous side pieces.

It was all going along swimmingly until Bill Sharon stumbled upon a partner who packed some heat.

Sharon became smitten with a young lady in 1880 named Sarah Althea Hill and—despite a 30-year age difference—they began to have an affair. Hill was a Missouri-born socialite who never met a fight she didn't look for, and kept a Colt revolver on her person at all times.

Sharon paid Hill for her "companionship" to the tune of $500/month, (about $15,000 today), plus a permanent room in the hotel next to his. (For the record, he stayed at the Palace Hotel, left to him by the drowned Ralston, as you'll recall, and Hill's room was at the adjoining San Francisco Grand).

When ol' Billy Boy attempted to break things off a bit over a year later, Sarah Hill wasn't having it. He tried to pay her off, but clearly didn't offer enough. She refused to vacate her room at the San Francisco Grand, and eventually only left after Bill Sharon had the hinges removed from her door and the carpet ripped up.

Sharon soon moved on to other women, Hill learned, and she was for sure not having that. In retaliation, Hill sued Sharon, alleging adultery. This presumed, of course, that they had been married, which—per Sharon and the public record—they had not.

That didn't stop Sarah Althea Hill, however, as she quickly produced a document as proof of the secret union, holding it above her head, yelling "Ah HA!!" She provided the perfectly reasonable explanation that Bill Sharon had not wanted a public declaration of their marriage so as to not upset all the mistresses he kept on the east coast, and thus they entered into a super-secret-off-the-books-shhhhh-I-promise-it's-for-real-we-just-can't-telllllllllllll-nobody kind of marriage. (We've seen a few of those with our clients, by the way.)

Bill Sharon claimed they were never married and the document to be a forgery. The State of California said, "Yeah, but... she's got a piece of paper, so... Says 'marriage' right on it. Right there, Bill. See? Do you see it?"

California courts supported Hill's claims and alleged that Bill Sharon would have to pay her alimony. Sharon, in return, filed an appeal with the U.S. Circuit Court.

Sarah Hill lawyered up, and one of her attorneys was this guy:

David S. Terry, former California Supreme Court chief justice, never left home without his bowie knife, so when he met pistol-packin' Sarah Althea Hill, it was love at first sight. He was a large man—especially for the time—at 6' 3" and well over 200 lbs, with a forked hairline, the beginnings of a mullet, and the goatee of an ungroomed poodle.

Now, Terry had stabbed a man in 1856 and was convicted, but then released. In his own iron-clad defense, Terry claimed he merely stuck the knife out in front of him and a man chanced to walk into it, whilst Terry chanted, "Why are you stabbing yourself? Why are you stabbing yourself?"

OK, the stabbing did happen but maybe we made the rest of that up.

Three years later Terry fatally shot his "friend," United States senator for the state of California, David Broderick, but was acquitted and, apparently, still able to practice law, which reminds us to remind all of y'all that the American West in the 1800s was bonkers. There needs to be a saying about that... something like the "Bonkers, Bonkers West." Fingers crossed that catches on and Will Smith makes a song about it.

In the circuit court case, the appointed judge was Stephen Johnson Field. He was the serving chief justice of the California Supreme Court at the time. Guess why! Go on... guess! He became chief justice on account of the former chief justice had recently murdered some dude in a duel and hightailed it out of the state.

Ain't them the breaks? You wait to see who's appointed to preside over your case, hoping it's someone who'll have your favor, see you and your client in a good light. And then of course it's the guy who got your old job on account of you murdered a guy in a duel—and he never even thanked you for it. What a jerk.

In case you're imagining this was an open and shut "she's-crazy-and-has-no-official-proof-of-marriage" type of case—ahhh, you'd be wrong. It dragged on long enough that it was still being fought in 1885, when Bill Sharon died, and then continued on further with representatives of his estate. You better believe when Bill shuffled off his mortal coil, Sarah Hill magically produced a secret will wherein Bill Sharon left her all of his possessions. How convenient.

Soon after Bill Sharon's death, Sarah Althea Hill married her attorney, David S. Terry. That's right; she married the dude who killed the other dude in the duel and was then representing her in court. They raised their respective weapons to the sky and dared anyone to stop them in their pursuit to marry and conceal carry.

But finally getting wed to somebody didn't satisfy Sarah's litigious needs. For 10 years, the robber baron battle of "were they/weren't they" known as "Sharon vs. Sharon" waged on and the newspapers loved it.

In an April 1884 edition of The Saint Paul Daily Globe, dramatic details of the ongoing court case were revealed.

Mrs. Hill? er, we mean, Mrs. Sharon? Mrs. Terry? Mrs. Hill Sharon Terry was accused in court of resorting to "sorceries" to get Bill to propose to her, and we all know what that means. [Insert 19th century eye roll... "Oh, great... here comes a lady... avert your eyes so she doesn't empty your bank account with her sorceries."]

Ex-Senator Bill Sharon's attorneys brought in surprise witness George Gillard, caretaker of a local cemetery, who alleged that Sarah Hill paid him in silver so that she might throw a bundle of clothing in the bottom of a grave prior to a body being buried therein. Because that's how you catch you a rich man, obviously. And apparently, that's what "sorceries" means.

Hill's team refuted this claim, and so they had Mr. Gillard disinter the body in question and—lo and behold—a bundle of men's clothing wrapped in newspaper was found underneath the coffin. There was no way to prove definitively that Hill was responsible for getting said bundle in the grave, however, and she swore to the court she had no knowledge of any of it. Because sorcerers tell lies.

Another allegation made by Sharon's lawyers was that Mary Ellen Pleasant, now largely considered to have been the first Black millionaire in the United States, had been enlisted by Sarah Hill to poison Bill Sharon's food. It is true that Pleasant helped bankroll Sarah Hill's lengthy court battle, and that she was a wealthy, successful, and well-known cook. Pleasant had made her fortune providing food and lodging for miners out west, and she invested her fortune cleverly in many different enterprises, including, drumroll, please... the Bank of California. Remember the Bank of California? What a coincidence!

Sharon's legal team didn't miss the opportunity to stereotype Pleasant as a voodoo lady and try to ensnare her in the mess that was Sharon vs. Sharon. It didn't take.

In 1888, Justice Field delivered his final verdict, definitively not in Sarah's favor. She took it pretty well, except for the part where she began yelling obscenities at the justice and reached into her purse for her revolver. Judges don't really like that it seems.

Justice Field ordered Hill to be held for contempt, and she was removed from the court, which her husband-attorney Stabby McDuel Guy DID NOT like. He grabbed his bowie knife, like you do, and threatened to kill EV-ER-Y-BODY. That landed him six months in jail. And just like that, Sarah Althea Hill Sharon Terry went from rooms in adjoining hotels to cells in adjoining prisons.

Just a totally random selection of lawyers who—like Dave Terry—did some crimes in the midst of trying to prove their clients didn't do any crimes. Oops.

The following year, in 1889, the Terrys just so happened to be traveling on the same train as Justice Field and his personal bodyguard, U.S. Marshal David Neagle. In a railroad station dining room along the route, the Terrys approached Justice Field. David Terry slapped the Justice, allegedly hard enough that he knocked Field's glasses clean off his face.

Marshal Neagle commanded Terry to stop. "Stop that right now, you!" he said, probably. Terry did not stop that, and Neagle shot Terry dead. Sarah Terry reportedly covered her husband's body with her own, whilst also surreptitiously removing his bowie knife from his person and sliding it into her own satchel, nestling it against her revolver, where it had always belonged. Gosh, love is sweet.

Sarah Terry spent the following years wandering around the streets of San Francisco, constantly in search of a way to commune with her dead husband, via seance and other various avenues of spiritualism. She probably did more sorceries, but it's hard to know for sure.

Ultimately, Mary Ellen Pleasant had Sarah Terry institutionalized in the Stockton State Hospital in March of 1892 at the age of 41. Terry remained there until her death, 45 years later, having spent more years in confinement than out.

She was convinced that she was an exorbitantly wealthy lady whose institution was her mansion, and the many orderlies and doctors her servants.

If there's a moral to the story here, it's, umm... convincing a cemetery caretaker to bury a newspaper-wrapped bundle of men's clothing in a grave underneath a coffin is not the most effective path towards generational wealth.

You're welcome.

Sources

"Beloved Bonanza King William Chapman Ralston," The Museum of the City of San Francisco (https://sfmuseum.org/hist10/wralston.html : 2 Oct 2024).

"Comstock Lode," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comstock_Lode : 2 Oct 2024).

"David S. Terry," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_S._Terry : 2 Oct 2024).

"Mrs. Hill's Sorcery," The Saint Paul Daily Globe, 3 Apr 1884, p. 3.

"Ralston at Rest," San Francisco Chronicle, 28 Aug 1875, p.3.

"Sarah Althea Hill," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Althea_Hill : 2 Oct 2024).

"The Sharon Family in California," Bill Putnam, (https://billputman.com/the-genealogy/sharon-related-families/index.html : 4 Oct 2024). "Sorcery and a Lawsuit," Savannah Morning News, 3 Apr 1884, p. 3.

"Stephen Johnson Field," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stephen_Johnson_Field : 11 Oct 2024).

"William Chapman Ralston," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Chapman_Ralston : 2 Oct 2024).

"William Ralston," FoundSF (https://www.foundsf.org/index.php?title=William_Ralston : 2 Oct 2024).

"William Sharon," Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Sharon : 4 Oct 2024).

"William Sharon, King of the Comstock: Parts I-IV," Michael McLaughlin, Tahoe Guide (https://yourtahoeguide.com/2018/07/william-sharon-king-of-the-comstock-part-ii/ : 4 Oct 2024).

Comments